The outdoors as medicine. How nature restores attention and wellbeing.

I have always found it difficult to explain why time outdoors feels so different to time spent anywhere else.

You leave the house in one state of mind, maybe carrying the weight of a hundred small tasks or still half-focused on your phone.

Then something shifts. After a mile of walking through a park, or half an hour sitting by the sea, your shoulders drop. Your breathing slows. It feels like your brain has switched channels.

It turns out this isn’t just a feeling. Science has been catching up with what poets, philosophers and walkers have been saying for centuries: nature changes the way we think and feel. More than that, it restores something that modern life constantly takes away.

Attention restoration and the science of focus

Psychologists Rachel and Stephen Kaplan developed what they called Attention Restoration Theory in the 1990s. Their idea was that natural environments help our brains recover from what they termed “directed attention fatigue.”

That is the kind of mental drain you feel after hours of emails, meetings, scrolling and task-switching. Urban environments often make it worse because they demand constant vigilance: crossing roads, navigating traffic, processing noise.

Nature, by contrast, offers what the Kaplans described as “soft fascination.” Think of the way a fire flickers, the sound of water running, or the patterns of leaves in the wind. These things hold our attention without exhausting it. They give our cognitive systems a chance to rest while still keeping us gently engaged.

Modern research backs this up. A 2015 study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showed that people who spent four days hiking in nature scored 50% higher on creative problem-solving tasks than those in urban environments. The combination of natural surroundings and time away from technology seemed to unlock something deeper in the mind.

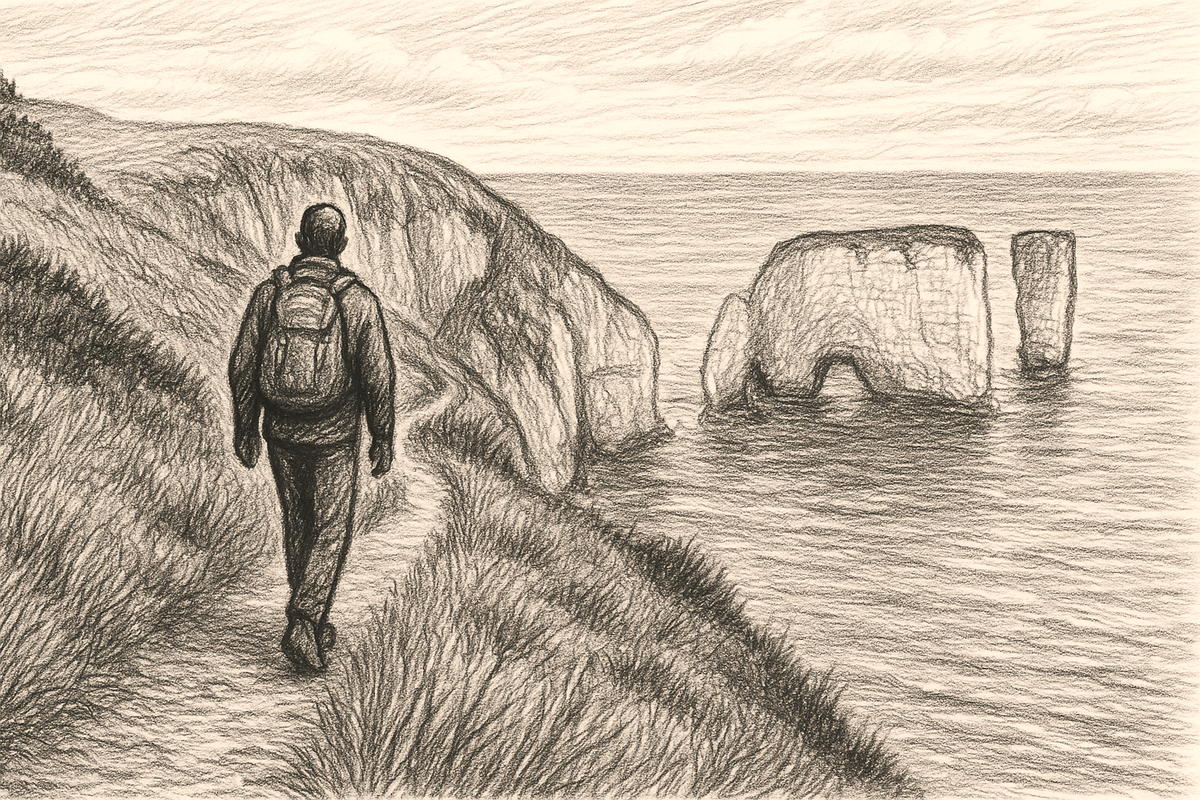

I have felt this first-hand. After a long week of back-to-back calls, sometimes the only thing that clears my head is a run on the trails in the New Forest or Purbecks. By the time I get back, I am not just less stressed. I am sharper, more creative, and more ready to face the things I had been avoiding.

The power of walking for ideas

Writers have always known this. Nietzsche claimed that “all truly great thoughts are conceived while walking.” Virginia Woolf described walking as “the most human of activities.” And Rebecca Solnit devoted an entire book, Wanderlust, to the cultural history of walking as a way of thinking.

There is something about the rhythm of walking that sets the brain loose. A 2014 study at Stanford University found that creative output increased by 60% when participants walked compared to when they sat still. The effect carried on even after the walk had finished. It didn’t matter whether the walking happened outdoors or on a treadmill. Movement itself sparked new ideas, but being in nature added something else: lower stress, higher mood, and a sense of perspective.

I can trace some of my best ideas back to walks where I had no plan other than to move. A couple of years ago, while working through a difficult decision, I found myself following a coastal path with no headphones, just the sound of the sea. Somewhere along that walk the answer appeared, not as a sudden lightning bolt but as a gentle realisation. Walking had given my brain the space to wander into clarity.

Nature as disconnection

Part of nature’s medicine is what it removes. There are no notifications, no meetings, no inbox to check. In natural spaces you are not being pulled into a hundred micro-demands for your attention. Instead you are left with silence, or birdsong, or the crunch of gravel underfoot.

Sherry Turkle, the MIT professor who has studied our relationship with technology, calls the modern condition “always-on.” We rarely allow ourselves to be unreachable. Yet it is in that unreachable space that our minds can rest.

The Mental Health Foundation found that 65% of people in the UK said being near green spaces had a positive effect on their mental health during the pandemic. When everything else in life felt chaotic and screen-based, parks, gardens and countryside became lifelines.

That appetite for presence is now shaping new experiences. Projects such as FForest in Cardigan or The Good Life Society in North Wales are not built on abundance.

They are built on slowing down. FForest offers a mix of woodland accommodation, communal eating, and outdoor swimming. The Good Life Society hosts festivals that strip things back to campfires, wild spaces, workshops and shared meals. Both frame nature as something restorative, not just recreational.

The wellbeing dividend

The health benefits are becoming impossible to ignore. A large-scale study from the University of Exeter, involving nearly 20,000 people, found that spending at least two hours a week in nature was strongly linked to higher wellbeing and self-reported health. The interesting part was that it didn’t matter whether the two hours were in one block or spread across the week. What mattered was simply making the time.

Exposure to natural light helps regulate circadian rhythms, improving sleep quality. Being outdoors reduces cortisol, the stress hormone. Even small interventions, like planting more street trees, have been linked to lower rates of antidepressant prescriptions.

The Japanese practice of shinrin-yoku, or forest bathing, has been studied for decades. Regular time in forests has been shown to lower blood pressure, reduce anxiety, and strengthen immune response. It is not mystical. It is physiological. Our bodies are wired to respond positively to the natural world.

Why this matters now

It is hard to ignore how relevant this feels right now. Many of us are working longer hours, sitting in front of screens for most of the day, and living in environments where distraction is the default. Our attention is pulled constantly in directions we did not choose. No wonder so many people are craving the opposite.

Walking, wild swimming, trail running, gardening - these are more than hobbies. They are ways of repairing ourselves. They give us back attention that has been fragmented, and they reconnect us with rhythms older than any algorithm.

For me, trail running is as much about mental clarity as it is about fitness. The physical act of running is part of it, but it is the woods, the mud, the changing light that bring me back into focus. I often return more restored from a ten kilometre run through the hills than from a weekend spent trying to “rest” at home.

A cultural and brand opportunity

The outdoors as medicine is not just an individual pursuit. There are wider cultural and business opportunities here too.

Some workplaces are beginning to introduce walking meetings as a norm. Universities are experimenting with phone-free study zones. City planners are talking about creating more quiet spaces in urban areas, places where people can simply sit without the intrusion of screens.

For brands connected to the outdoors, lifestyle, or wellbeing, there is a chance to lead. Helping people to switch off and spend time in nature is no longer niche. It is becoming a cultural expectation. Just as sustainability reshaped fashion and food, nature and disconnection are reshaping how people think about value.

A personal note

I have lost count of the times I’ve gone outside in a bad mood and come back feeling different. Sometimes it is only a subtle shift, but it is there. On one occasion I remember walking in the rain, soaked through, grumbling to myself. By the time I got home I was laughing at how ridiculous I looked, but the stress I had been carrying all day was gone.

The outdoors does not need to be grand to work its medicine. You don’t need the Himalayas or the Pacific Crest Trail. Sometimes a walk to the end of the road, or a sit in a local park, is enough. The point is to be there, to notice, and to let your brain unwind.

The outdoors is not an escape from life. It is part of life. It is not something we can relegate to the odd holiday or weekend trip. It is a daily medicine, free and available to anyone willing to step outside.

In a culture that keeps asking us to do more, the most radical act might simply be to do less. To step into a green space, to walk without headphones, to breathe deeply and let the world slow down.

Because in the end, nature does not just restore attention. It restores us.